For reference purposes it is important to note that this book review and supplemental video were originally completed as a Book Context Assignment for Michael’s The Hyperlinked Library course, taught in the Fall of 2015 at San Jose State University.

Socially Isolated

Addicted young people

Few real-life social ties

These are just a few of the phrases used to describe the traditional “lonely gamer” in the article The “lonely gamer” revisited by Diane Schiano, Bonnie Nardi, Thomas Debeauvais, Nicolas Ducheneaut, and Nicholas Yee. This has been the stereotype of the traditional gamer for the past two decades.

However, Jane McGonigal, a New York Times bestselling author and world-renowned game designer would argue otherwise. In McGonigal’s 2011 book Reality is Broken: Why games make us better and how they can change the world, she explores the positive benefits that games can have on people’s everyday lives and how gamers are connecting socially and intelligently to create a better world.

As libraries seek to transition into the role of Library 2.0 we must be willing to listen to our users and understand their needs. According to the PEW Research Center’s report titled Adults and Video Games, written by Amanda Lenhart, Sydney Jones and Alexandra Macgill, 53% of Americans aged 18 or older play video games while one in every five adults play video games on a daily basis. If we turn our attention to teens, a staggering 97% of teens play video games. Games offer us an exciting and engaging opportunity for us to connect with our users in a more positive way and in a way that they feel more involved. If so many of our users are turning to games as a form of entertainment and social connectedness, we as librarians would be wise to look closely at how games are engaging users in a positive way.

McGonigal combines her extensive experience in the gaming industry with well researched psychological theories to explore why games make us happy and how we can apply 14 ‘fixes’ to reality. McGonigal argues that these ‘fixes’ would make for a much more engaging and rewarding reality. If you would like to explore McGonigal’s 14 fixes in greater depth, I would recommend you read the book in its entirety as it reads well for gamers and non-gamers alike. For the purposes of this post, I will be exploring only a handful of the 14 fixes that I feel could be applied effectively to library space to better engage users and promote a more participatory Library 2.0 experience.

According to McGonigal, there are countless forms of games for players to engage in, these range from single player to multiplayer to even massively multiplayer games, some of which take no more than five minutes to play and others that can involve a much more extensive time investment to play. Although games come in diverse forms, McGonigal outlines four key traits that all games have in common at their most basic level.

The Four Defining Traits of Games

First, all games have a goal. By providing players a goal the game gives them something to work towards. As McGonigal says, this goal is a sense of purpose.

Secondly, all games must have rules. These rules give the player the foundation for how they are expected to accomplish the goals set out for them by the game.

Thirdly, for games to be effective they must have a feedback system. A feedback system allows users to quickly evaluate how well they are doing in relation to meeting their goals.

Finally, games must have voluntary participation. Users must feel in control of their participation in games. This is one of the most important aspects of games; the ability for players to enter and leave a game at will ensures that they are in a safe environment.

These traits form the basis of all games, and it is upon these that McGonigal has derived her ‘fixes.’ I have chosen to explore three of these ‘fixes’ in more detail below.

Fix # 3: Do more satisfying work

“Compared with games, reality is unproductive. Games give us clearer missions and more satisfying, hands-on work” (McGonigal, 2011, p. 55).

According to McGonigal, creating more satisfying work begins with two important things: a clear goal and actionable next steps. By clearly presenting a goal we are able to know exactly what it is we are being asked to accomplish, while actionable next steps ensure that we know exactly what is expected of us to ensure that we succeed in that goal.

According to McGonigal, one game in particular does this extremely well. World of Warcraft is a popular massively multiplayer game created by Blizzard Entertainment. Players navigate a massively online world completing quests, leveling their characters and working in teams of 5, 10 and 25 players to overcome huge tasks impossible to complete on their own. When players accept a quest from one of the thousands of non-playable characters (NPCs) in the world, they are presented with a clear goal with actionable next steps.

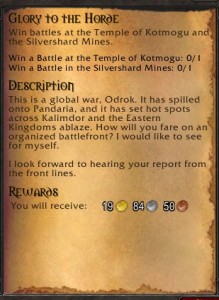

Quest in World of Warcraft: Glory to the Horde

Above you can see an example of a World of Warcraft quest called Glory to the Horde. The goals for the quest are clearly outlined. Players are being asked to win two battles at two very specific locations. The actionable next steps are clear: take part in the battle and lead the team to victory. Another reason this work is so satisfying in this virtual world is that the rewards for completing quests are very clearly identified, making completing the quest more fulfilling.

According to McGonigal, there are almost endless series of quests in World of Warcraft. It is the clearly defined goals and actionable next steps that make World of Warcraft so engaging with players and make the work they are doing more satisfying.

Fix # 5 Strengthen your social connectivity

“Compared with games, reality is disconnected. Games build stronger bonds and lead to more active social networks. The more time we spend interacting within our social networks, the more likely we are to generate a subset of positive emotions known as “prosocial emotions” (McGonigal, 2011, p. 82).

Prosocial emotions, according to McGonigal, include love, compassion, admiration, and devotion. Essentially, any feel-good emotions that can be directed to others. Although games don’t evoke these emotions on their own, they are an added side effect of playing games in social networks, such as Facebook, and I would argue in many face to face games, like chess or Monopoly.

When playing games through social networks, many of them allow you to trash talk your opponent by posting to a chat window or to their virtual profile. Although trash talking normally carries a negative connotation, McGonigal argues that research shows that playful teasing is one of the fastest and most effective ways to create positive feelings toward another person (McGonigal, p. 84). Dacher Keltner, a researcher at the University of California argues that teasing feels good because it builds trust and makes us more likable.

While McGonigal primarily focuses on video games, I think almost anyone who has played any kind of game (video game or board game), has had a playful teasing experience. It is these social encounters that help games promote social connectivity to the people around us.

Fix# 8 Seek meaningful rewards for making a better effort

“Compared with games, reality is pointless and unrewarding. Games help us feel more rewarded for making our best effort” (McGonigal, 2011, p. 148).

According to McGonigal, real life just doesn’t give us the feedback we need to feel rewarded on a daily basis. Although this fix isn’t necessarily tied to a game in the traditional sense, it does apply game mechanics to everyday activities.

McGonigal once joked while doing a presentation at a technology conference that she wished she could receive instant feedback after doing a presentation like she got after playing a game. For example giving a good presentation would award her +1 Presentation Skill, after helping stick up for someone you would receive +1 Backbone, etc.

A few days after the conference she received an email from Clay Johnson, the director of Sunlight Labs, a community of open-source developers looking to make the government more transparent. He attended her presentation and quickly coded a website that allowed people to send +1’s to people for a wide variety of different tasks and attributes. If a user signs up for the service, all their +1’s stack to create a very game-like profile for yourself. It is this idea of meaningful visual rewards that can help encourage people to put forth a better effort.

Gaming may be fun but how can it be utilized in the library?

So how can librarians use this book to better serve our patrons? As I mentioned earlier, a large number of Americans are already playing games, and it isn’t just kids. Adults and seniors are also playing games and in many cases they are playing games more frequently on a weekly basis (Lenhart, Jones, & Macgill, 2008). According to Library 2.0: A Guide to Participatory Library Service, written by Michael E. Casey and Laura C. Savastinuk, libraries are “losing the interest of our users, [w]e no longer consistently offer the services our users want, [w]e are resistant to changing services that we consider traditional or fundamental to library service” (Casey & Savastinuk, 2007, p. xxiv). By utilizing the ideals presented by McGonigal, libraries can create more engaging ways to get users to participate in library services.

Children’s librarians could implement World of Warcraft style quests for book clubs, as outlined in McGonigal’s fix #3. They could ask teens to read a certain number of books per week and present them to the librarian for their rewards. Libraries could invite people into the library to take part in board game nights to strengthen social connectivity as outlined in fix #5. This would build trust within certain library communities.

It is for these reasons that libraries can look to video games and the gamification of services to create more engaging experiences for our users. By exploring Reality is Broken, by Jane McGonigal, information professionals will gain a better understanding of the positive psychological impact games are having on players around the world and how they are positively influencing user experiences. McGonigal’s ‘fixes’ can be used to create stronger participatory services to library users by providing a unique engaging experience using game mechanics.

Supplemental Video

References:

Casey, M. E., & Savastinuk, L. C. (2007). Library 2.0: A guide to participatory library service.

Lenhart, A., Jones, S., & Macgill, A. (2008). Adults and Video Games. PEW Research Center.

McGonigal, J. (2011). Reality is broken: Why games make us better and how they can change the world. New York: Penguin Press.

Schiano, D.J., Nardi, B., Debeauvais, T., Ducheneaut, N., & Yee, N. (2014). The “lonely gamer” revisited. Entertainment Computing, 5(1), 65-70 http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.entcom.2013.08.002

References for Video Supplement:

Lenhart, A., Jones, S., & Macgill, A. (2008). Adults and Video Games. PEW Research Center.

McGonigal, J. (2011). Reality is broken: Why games make us better and how they can change the world. New York: Penguin Press.

Media Evolution. (2011). Gamification- how we can use game mechanics in areas that are not a game.

Rolighetsteorin. (Oct. 15, 2009). Bottle Bank Arcade. Retrieved from https://youtu.be/zSiHjMU-MUo

Ryan lives in Ottawa, Canada and is currently obtaining his Master of Library and Information Science (MLIS) degree at San Jose State University. He has a Bachelor of Arts in History and a Minor in Communication Studies. Prior to his MLIS, Ryan received his Library and Information Technician diploma and has been working in the library field for four years. He currently works at Carleton University MacOdrum Library. His interests include: emerging technology, big data, copyright, open access, and information literacy.